运用专利制度对抗“生物海盗”行为

保护中草药处方

Use Patent Protection against

Global Biopiracy of TCMK

作 者:韩 皓

摘 要 · Brief 从《神农本草经》到《黄帝内经》,从《本草纲目》到《伤寒论》诸多古籍,从扁鹊、华佗、张仲景到孙思邈、李时珍等名医,再到蒙、藏、壮、瑶、苗、回、朝等多个传统医学体系,我国中医药传统文化数不胜数。中国首位诺贝尔医学奖获得者、中国中医科学院首席研究员屠呦呦曾表示,中医药学是一个伟大的宝藏,从神农尝百草开始,在几千年的发掘中,积累了大量的珍贵的临床经验和传统处方。作为国宝,中医药学理以及处方成果应得到重视、发掘和保护。然而,从目前来看,中医药学的知识产权保护短板明显,甚至让我们失去了不少主动权。《世界专利数据库》统计资料显示,在世界中草药和植物药专利申请中,中国的中药专利申请仅占 0.3%,日本已抢注了全球中成药 7 成以上的中药专利。到目前为止,日本已申请了《伤寒杂病论》、《金匮要略方》中的 210 个古方专利。在韩国,朝鲜时代医学书籍《东医宝鉴》列入世界记忆遗产名录。据世界卫生组织(WHO)统计,目前全球约有 60%的人使用中草药治疗疾病,每年国际中药销售额高达 160 亿美元。国外所用的中医药有 70%至 80%从我国进口,然而,他们进口的中成药比例不足 30%,其他都是原料药,且价格低廉。同时,越来越多的外国公司和研究机构通过在中国成立分公司或办事处、举办国际研讨会、学术交流会、与我国药企建立合资厂或技术合作,收集中医药技术信息,以期盗窃具有独特疗效的传统中医药秘方。发达国家对中医药传统知识的不当侵害,使处于“公知领域”的中医药传统知识面临流失,潜藏着可能损害中医药可持续发展并威胁国家安全和利益的严重隐患。仅管对于中药产业知识产权保护的呼声日高,但目前中药领域的知识产权保护仍然非常脆弱,尤其是我们的中药保护脱离了国际现行的知识产权制度。利用我国传统医药知识无偿获取商业利益的“生物海盗”(Bio-Piracy)行为在国际上正日益增多,利益损失及其危害无法估算。因此,结合中医药学的自身特点,健全完善现行中医药知识产权保护制度势在必行。本文试图探讨如何建立一个更加平衡和灵活的保护“中草药处方”(TCMK)的专利制度以对抗日益猖獗的国际“生物海盗“行为。I

Introduction of TCMK

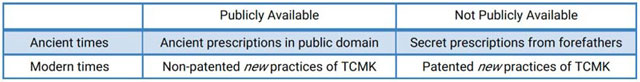

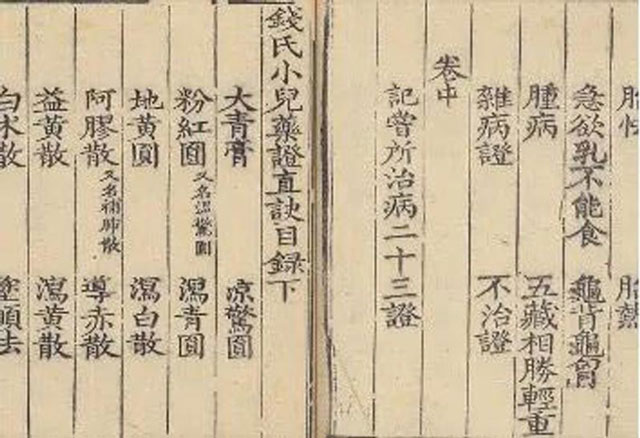

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is a sum of health-care practices in China, which achieves health by restoring a patient’s internal yin-yang equilibrium via herbal remedies or physical manipulation.1 TCM has a history of more than 3,000 years in China and the earliest documentations of traditional Chinese medicine can be dated back to 1,100 B.C.2Although embracing a wide range of practices, TCM features prominently prescriptions over herbal medicine. The Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders, for example, an early TCM text compiled in the Han Dynasty, included 112 herbal prescriptions;3 Compendium of Materia Medica, written during the Ming Dynasty, contained 11,096 prescriptions. These prescriptions, referred to in this article as ancient prescriptions already in the public domain, typically include a combination of various herbal ingredients necessary to generate specific and synergistic therapeutic effects. In contrast, Western medicine typically focuses on one single chemical agent and hence the limitation of this approach has been recognized.4 As a result, the value of TCM prescriptions has begun to draw more attention in the biomedical research community, despite the fact that some continuingly deprecated TCM as quackery. It has been reported that TCM, including herbal mixtures, has gained in popularity in the West.5 In 2012, for example, global sales of Chinese herbal medicine reached US$83 billion, up more than 20 per cent from 2011.6 Nowadays, moreover, TCM account for approximately 40% of all health care delivered in China and thereby is instrumental in keeping more than 1.3 billion Chinese people in reasonably good health with comparatively small funding.7 In this article, accordingly, Traditional Chinese Medicine Knowledge (TCMK) refers predominantly to TCM prescriptions, which are one of the most important heritages of Chinese culture and can be classified according to public availability and time of emergence in Table 1.Table 1 Typology of TCMK

(An ancient prescription in the

Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders)II

Biopiracy of TCMK

Ironically, on the one hand, Western medical science has grudgingly accepted alternative healing systems; on the other hand, western pharmaceutical industry desperately sought TK related to genetic resources and medicine new drugs sources.8 CAS,9 for example, recognized that there is an accelerated interest in mining the rich lode of TCMK due to reduced side effect in TCM, effective alternatives to drug-resistant disease,10 and decreased cost in light of the reality that new drugs need take years to get through the research and development pipeline at enormous cost. It has been found, for example, that "using traditional knowledge increased the efficiency of screening plants for medical properties by more than 400 percent"11 It is, therefore, not surprising that a considerable number of pharmaceutical companies utilized TCMK as intermediaries for developing new drugs. The best known example is artemisinin, which is extracted from artemisia annua (Chinese sweet wormwood) based on TCMK and is the basis for the most effective malaria drugs in the world. The Centre for Novel Agricultural Products’ Artemisia Research Project, at the UK’s University of York, for instance, is developing high-yielding varieties of A. annua. It recently announced the registration of a new hybrid variety in China, the first A. annua variety bred outside the country to be registered. 12In context of traditional knowledge (TK), “biopiracy”, albeit with vagueness, may refer to unauthorized commercial use of TK, or “patenting of spurious inventions based on such knowledge without adequate authorization and compensation.”13 This failure to recognize or compensate TK holders for inventions arising out of their biocultural TK is a key feature of biopiracy distinguishing it from “bioprospecting.” In a global context, therefore, biopiracy has been viewed as a form of thievery, perpetrated by countries in the North against cultures in the South and performed at the expense of developing countries.14 Accordingly, global biopiracy usually refers to the asymmetrical and unrequited movement of TK from the South to the North through the patent system, given that cases of biopiracy are most commonly associated with the grant of a patent over some products or derivatives based on TK.15As Data Migketay Victorino Saway of the Talaandig tribe of the Philippines enunciated, "The collection [of our biological resources] gravely transgressed our sacred customs and traditions… It grossly violated our cultural rights, pirated our local wisdom, knowledge and property, and suppressed our survival and identity."16 The greatest criticism of biopiracy, however, centred on unfairness, especially in economic terms.17 Pharmaceutical companies in the North, for example, are permitted to realize millions of dollars in sales from patented products based on traditional medicine knowledge in the South with little or no payment, thereby contravening global distributive justice.To make matters worse, biopiracy sometimes constituted unjust enrichment of outsiders at the expense of TK holders.18 Biopiracy through the patent system, for example, served to exclude further sale or export by the original producer (often the original knowledge-providers) in the South and thereby deprive developing countries of the chance to commercially profit from their traditional knowledge within the world economy.19 South Korean pharmaceutical companies, for example, developed a new product called Heart Rescuing Teapills. It was a huge commercial success and made over 70 million US dollars from its revenue. They are also exported to many other Asian countries, including China, which led to fierce competition with similar TCM products in China. TCM practitioners and scholars, however, found out that the formula drew heavily on the formula of Six-Ingredient Spirit Teapills from TCMK and therefore condemned this spurious invention as an outrageous steal.20III

International Patent

Regimes and Biopiracy

A. The Interplay between

Patents and Biopriacy

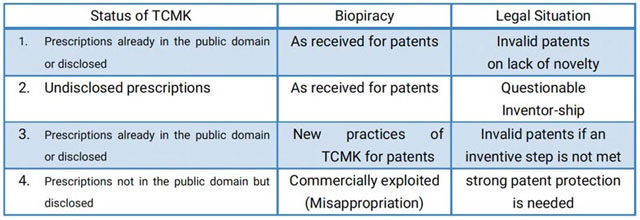

Cases of biopiracy are most commonly associated with the granting patents over inventions derived from or based on TK. A recent WIPO IGC consultation paper confirmed that “a significant number of patent applications concern inventions which are in some way related to traditional knowledge.”21 In such situations, accordingly, the relationship between the patented inventions and their underlying TCMK may be the key to understanding patent-based biopiracy of TCMK. In my opinion, four categories of biopiracy related to patents can be identified and nuanced as follows:(1)Direct biopiracy, which refers to situations where TCMK that is disclosed or already in the public domain, such as ancient prescriptions published in ancient pharmaceutical texts (etc Compendium of Materia Medica), becomes patented, as received, due to failing to identify relevant prior arts in the examination of the patent examination.

(2) Inventor-ship biopiracy, which refers to situations where certain TCMK, for example, zu chuang mi fang (secret prescriptions from forefathers), which is not public available, is patented, as received, without authorization from and or compensation to the holders of that TCMK; consequently, it is possible to challenge those patents on the basis of questionable inventor-ship, as opposed to lack of novelty. A patent application claims a combination of known traditional ingredients, with the claim that it has a surprising therapeutic effect. This surprising effect may have been disclosed by a TCM practitioner, who had discovered it during the course their (sic) own experimentation and adaptation of traditional healing methods. In this case, the TCM practitioner may be the actual inventor, and the title to apply for a patent may need to be legally derived from that person.22

(3) Refined biopiracy, which refers to situations where TCMK, disclosed or already in the public domain, is dubiously improved on or modified for patents, absent an inventive step. In these situations, that is to say, “something alleged new has been created that represents an addition to but that derives from the previously available pool of knowledge.”23 New practices of TCMK can, therefore, be described as new knowledge created by new generations who based their inventions on TCMK already in the public domain. For example, US patent No 6,352,685, which relates to an extract of kwao krua for use in a cream or gel to be applied to the skin, was found to be a fairly obvious extension of practices already described in Luang Anusarn-Sounthorn’s texts.24

(4) Misappropriation biopiracy, which refers to situations where commercial companies profitably exploit TCMK already disclosed due to, for example, patent disclosure requirement, but not in the public domain, without any benefit-sharing with relevant TCMK patents holders. In such cases, arguably, strong patent protection of TCMK is needed.

Table 2 Typology of TCMK Biopriacy

B. Patent Systems under TRIPs:

How International Patent Regimes

Facilitate Biopiracy

Professor Ikechi Mgbeoji noted, “[t]he appropriation of plants and TKUP through the patent system presents itself as a respectable business fully supported by the paraphernalia of apparent legality.”25 He, therefore, imputed global biopriacy partly to the changes brought about by the TRIPs agreement on the ground that it permits patents to be issued with incredible ease and with minimal regard for the origin of traditional knowledge.26 Foreign corporations and researcher in the North, for example, are able to meet the TRIPs patent requirements of novelty, inventive step and utility by mixing their scientific and technical expertise with certain aspects of the appropriated traditional knowledge or with the extracted active ingredients from native biological resources based on TK in the South without or little compensation.27 Thus, at the heart of global biopiracy is a struggle over economic profits derived by industries in North through TK-based patents; it has been suggested that critical attention must be paid to the Western scope of the concept of patentability, the Western basis of the patent concept itself, considering that the industrial countries in the North normally use economic leverage to coerce developing countries to institute overreaching Western patent regimes through such international conventions as the TRIPs, which is arguably “a product of the immense clout of the American pharmaceutical and biotechnology.”28Paradoxically, however, neither the TRIPs agreement, nor any other relevant international legal instrument, has articulated a binding, authoritative or definitive interpretation of the key elements of a global patent system. That is to say, on a strict analysis, “None of the key elements of patentability, especially the concepts of ‘novelty’ and ‘invention’, has any globally accepted definition.”29 Thus, the TRIPs left industrial countries in the North to free to define patentable inventions and lower patentability standards, so that patent systems in the North arguably facilitated the appropriation of TK in the South. In effect, despite the emphasis of contemporary patent law on the trend towards globalization, national patent systems in the North have always been predicated mainly on economic considerations.30

1. Debates over “products of nature”

In recent times, “[t]he genomics gold rush revolves around genes that have been isolated and purified outside an animal, plant or micro-organism”,31 after Diamond v. Chackrabary,32 as a landmark decision, opened the floodgate and obscured the line between “products of nature” and “artificial inventions” by holding that patents may be awarded to “anything under the sun that is made by man.” As a result, patents on purified natural substances and plants extracts derived from TK are becoming routine on the ground that these simple processes of isolation and purification are sufficient, or sufficiently unnatural, to give the gene the necessary amount of novelty to be patentable. However, as Thomas Kiley criticised, “there is nothing in the patent statute that says old substance becomes ‘new’ when first offered in purified and isolation form. This is law that judges have engrafted on the statute.”33 It follows that prejudiced Western statutory interpretations on products of nature functioned in favour of industrial countries in the North gratuitously pirating TK in the South.Such criticisms, of course, found an echo in many developing countries, such as Mexico, Argentina and Brazil, which do not allow the patenting of naturally existing materials. Brazilian patent law in particular stipulates that no patent shall be granted to living beings or “biological materials found in nature”, even if isolated, including the “genome or germplasm” of any living being.34

2. Debates over novelty

The concept of novelty in patent law of the North sometimes operates to disregard TK when the issue of novelty is addressed by patent examiners in industrialized countries. The real problem is that under current international law, for example, the TRIPs, there is not a global and specific standard of novelty. In the Canada, 35 the issue of prior art is considered on a global scale; in contrast, the US, for example, prior to the passage of the America Invents Act(AIA),36 considered prior art in domestic terms,37 whereby TK in a foreign countries, in order to count as prior art, must be patented or described in a printed publications; 38 undoubtedly, this facilitated the theft and patenting of TK from foreign countries and carried the consequence that foreign countries that do not permit the patenting of TK can provide no bar to a patent being obtained in the US.The AIA, however, removes the "in this country" limitation that used to apply to the "public use" and "on sale" bars. As a result, prior art for patents issued "will no longer have any geographic limitations,"39 and thereby public use of TK anywhere in the world renders it prior art to all subsequent U.S. patent applications. Nevertheless, practical considerations significantly limit the effect that the Act will have on the patentability of traditional knowledge. That is, the American regulatory system is likely to narrow the practical-as opposed to the statutory-scope of prior art.40 For example, even if certain TCMK in China may qualify as prior art under AIA, they will not have that effect at the administrative level unless the patent examiner knows of that TCMK. To make matters worse, as demonstrated by pharmaceutical companies' responses to traditional knowledge databases, these companies are likely to move towards combining active ingredients derived from certain traditional knowledge with more synthetic elements, to the effect this TK is not prior art that anticipates the new drug, thus avoiding novelty and non-obviousness issues.41

3.Debates over inventive step

“Inventive step” standard requires that the claimed invention be non-obvious for a person with ordinary skills in a given technical field. This means that TK-based inventions, even if novel, will not be patentable if it is lacking an inventive step from TK already publicly available. However, “A person with ordinary skills” is a legal fiction; patent offices and courts may apply different standards, according to the technical field concerned. Thus, something that may be obvious to a professional trained in TCM may not be so for somebody trained in the Western medical tradition.42 Accordingly, lax patent systems in the North, through a parochial standard of inventive step, grant patents on cosmetic rearrangement of chemical structure of a biological compound already identified by TCMK. To make matters worse, it is likely that courts in the North tend to assess obviousness through the lens of Western medical knowledge without regard to vast philosophical differences between TCM and Western medicine;43 for example, hence, substitution of some herbal ingredients in a existing multiple herbal prescription (fufang) obvious within a TCM system may be deemed “inventive” and patentable in the North. As a result, some purported “new” drugs in the North are no more than an attempt to weave an implausible inventive step into existing traditional therapeutic knowledge in the South.In light of this, some scholars, such as Samuel Oddi, called for a stricter non-obviousness hurdle to patentability and recommended that the test for inventive step should be “whether the claimed invention would be non-obvious to a person skilled in that art anywhere in the world.”

Policy Considerations for

Fighting Biopiracy

As Professor Michael Blakeney has noted, on the one hand, "Western patent systems grew out of a particular model of innovation at a particular time in history".45 Patent systems under TRIPs , thus, may not fit neatly with the sort of collective ownership of rights as practiced in many communities, where the 'invention' was made a long time before and its origins are not easily attributable to one individual or entity.46 For example, such ancient prescriptions as in Treatise on Cold Damages Disorders, by definition, are centuries-old so as to automatically fail the requirement of novelty with the meaning of Western patent system and is the cultural heritage of China already in the public domain. Moreover, some scholars found that an assessment of traditional knowledge, from a distributive justice perspective, may lead to the conclusion that an exclusive intellectual property right in traditional knowledge is not be the most appropriate response to the problems of bio-piracy,47 in that the main rationale for protecting TCMK against biopiracy is simply to “promote the fair and equitable sharing and distribution of monetary and non-monetary benefits arising from the use of traditional knowledge.”48On the other hand, some scholars criticized the view that rejects IP protections for TK on the ground that this would shrink the public domain as Eurocentric.49 Professor Graham Duttfield, for example, argued that traditional knowledge holders have their own regimes to regulate access and use of knowledge, and not every TK in the public domain should be in the public domain.50 Furthermore, it has been suggested that the benefits of open access to TK go to the wealthy and powerful; this may support the need for some form of property protection for traditional knowledge against biopiracy.51In my opinion, however, the key lies in whether IP rights in TK is the best solution for redressing TK biopiracy-related distributive injustice, at the expense of upsetting the fundamental balance which IPRs strives to maintain between incentives to original innovations and public domain for further innovations. Accordingly, some concerns over positive patent protection of TCMK must be addressed beyond the North–South cultural divide.The first is the access concern. the introduction of positive patent rights in TCMK means a retraction, at least with respect to ancient prescriptions which have been shared among TCM practitioners for thousands years. A solid public policy rationale should, therefore, be provided for limiting free use of such information as contained in ancient prescriptions.52The second is the innovation concern. Today's innovators build on the efforts of earlier innovators; the often-incremental nature of innovation, therefore, poses a serious challenge to the argument for positive IP protection of TMCK, considering that to grant a positive enforceable IP rights in ancient prescriptions already in the public domain would be likely to stifle future innovations built on those prescriptions.53The third is the “Right War” concern. Asserting positive IP rights by China in ancient prescriptions might trigger a global “Right War” on TK, given that developed countries are as rich in TK as developing countries and therefore they could claim IP protection of their “TK”, such as espresso in Italy, as developing countries did.54 A "Rights War" on traditional knowledge is not desirable from a global perspective, in that it might be difficult to ascertain the boundary of such rights and, more importantly, it would seriously constrain global knowledge exchange and fair competition.55Accordingly, it is arguable that the importance of the protection of TMCK against biopiracy should be weighed against the consideration of promoting the progress of science and useful arts.56 A patent system ought to recognize and respect contribution of TCMK while protecting interests in gaining free access to TCMK for future innovations. In other words, it is fundamental, in providing the patent protection for TCMK, to seek to strike a balance between the deterring TCMK-based biopiracy and the incentivizing TCMK-based innovations.57 It has been argued, for example, if the goal of access to affordable knowledge and information is a worthy one, then an assessment of traditional knowledge from a distributive justice perspective leads to the conclusion that IPRs in TK already in the public domain may not be the most appropriate response to the problems of bio-piracy.58In this article, I will, in light of the concerns above, advocate for a two- pronged approach to the patent protection of TCMK, namely, defensive patent protection of TCMK already publicly available against the biopiracy of category one and two in Table 2 and positive patent protection of new practices of TCMK against the biopiracy of category three and four in Table 2.V

Defensive Patent Protection

against Global Biopiracy

-advantages and challenges

Ancient prescriptions except secret ones cannot secure positive patent protection due to the lack of novelty. However, defensive patent protection intends to prevent outsiders59 from obtaining or exercising invalid patent rights over the TCMK already publicly available by ensuring that the relevant TCMK is taken fully into account as prior art when a patent is examined for its novelty and inventiveness, although this does not amount to a recognition of IP right over TCMK.60Normally, defensive patent protection has two aspects. One aspect is legal: to make sure that the criteria defining relevant prior art apply to the TMCK; the other aspect is practical: to make sure that TCMK is likely to be found by global patent examiners in a search for prior art.61A. Disclosure of OriginOn the legal side of defensive patent protection, patent law ought to be modified to accommodate better the role of TCMK as prior art. “Disclosure-of-origin” requirement which can be defined as “the obligation to identify, where necessary, the origin of resources covered by IPRs claims”,62 will take the center stage of this modification. Article 29 of TRIPs, which provides that “an applicant for a patent shall disclose the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for the invention to be carried out by a person skilled in the art...”, seems to support such this requirement given that the disclosure of origin is arguably necessary to describe fully the background of TK-based inventions.It seems that two types of the disclosure of origin are required for protecting TCMK against biopiracy.Version one:

“mandatory disclosure”Arguably, the discourse of origin requirement in the patent system must be mandatory to have any significant effect. Therefore, failure to disclose or dishonest disclosure of origin of TCMK ought to have one or some of the following consequences: the patent application would not be accepted; it would be rejected during the prosecution stage; if granted it would not be enforceable; or if granted it would be revoked with possible criminal sanctions for wrongdoers.63 The burden of compliance should be placed on the patent applicants and the patent granting offices.Version two:

“proof of legal acquisition”The disclosure of origin also aids in ensuring that the patent applicant has obtained the prior informed consent of the TMCK, and it monitors enforcement of access and benefit-sharing obligations in conformity with Article 8(j) of the CBD.64 The version ties the patent system more closely to the CBD’s ABS provisions by requiring patent applicants to submit with their application official documentation proving that TCMK were acquired in accordance with such obligations as prior informed consent or benefit-sharing arrangements. 65 For example, the Indian Biological Diversity Act, 2002, requires patent applicants for inventions based on genetic materials of Indian origin to obtain the prior informed consent of the National Biodiversity Authority, and it permits the Authority to impose benefit-sharing fees or royalties on the commercial use of the invention.66However, as far as ancient prescriptions already in public domain are concerned, it is more appropriate that the ABS arrangement for those prescriptions would serve as a basis for voluntary contractual arrangements, rather than as part of requirements in application for patents.67 In contrast, ABS arrangement should be mandatory for patent applications based on the new practices.68 For example, if a new drug is developed by a Western pharmaceutical corporation based on new prescriptions of TMCK, it may be appropriate from a distributive justice perspective to pay for their contribution, irrespective of whether or not those new prescriptions have been patented themselves.B. TK Documentation (TKD)As Kongolo and Shyllon noted, "the fact is that knowledge that is claimed to have been 'invented' and hence 'patented' and converted into intellectual property is often an existing innovation in traditional or indigenous knowledge systems".69 On the practical side of defensive patent protection, therefore, the information about TCMK must be available to the public to count as prior art and can be found easily by both researchers and patent examiners. One of the most effective ways to achieve the objective of availability is establishing an accepted TK database.70Indian TKDL, for example, containing 34 million pages of formatted information on some 2,260,000 (0.226 million) medicinal formulations in multiple languages, is a unique repository of India’s traditional medical wisdom. India, by virtue of the TKDL, has succeeded in bringing about the cancellation or withdrawal of 36 applications to patent traditionally known medicinal formulations.Inspired by Indian TKDL, China has developed two TCM databases, namely, China TCM Patent Database and the Chinese Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System (TCMLARS). The former was developed within the State Intellectual Property Office of China initially to assist patent examiners. It now exists also in English and is fully accessible to the public. The database includes over 22,000 patent records dating from 1985 to the present and 40,000 Traditional Chinese Medical formulations. The latter, which is administered by the Academy of Traditional Medicine, is a database of information contained in more than 800 biomedical journals published in China since 1984, and it currently contains about 68,000 records, which are all extensively indexed. A portion of TCMLARS exists in English.71However, debates exist as to whether TK documentation should be published or maintained in a state of secrecy. On the one hand, someone argued that traditional knowledge can best be protected, both from erosion and biopiracy through publicity but not secrecy. On the other hand, unlimited and unrestricted accessibility to this documentation leads critics to question whether TKD would effectively prevent biopiracy or facilitate biopiracy.72One way to avoid the risk of being a double-edged sword is to limit disclosure to selected parties. The TKDL, for example, is available to patent officers that have signed a TKDL Access (Nondisclosure) Agreement. Under such an agreement, patent examiners may use the TKDL for search and examination purposes only. The contents of the TKDL can only be revealed to third parties for the purposes of citation.73 Accordingly, TCMK already disclosed or already in public domain, such as ancient prescriptions ought to be incorporated into more accessible databases for the purpose of aiding patent authorities against biopiracy, whereas confidential registers should be established for non-patented new practices of TCMK and secret prescriptions.Nevertheless, Traditional Knowledge Documentation is often ineffective to invalidate such patents as purified natural substances or plants extracts in that they are often not clearly identified or sufficiently described in the TCMK.VI

Positive Patent Protections

against Global Biopiracy

-advantages and challenges

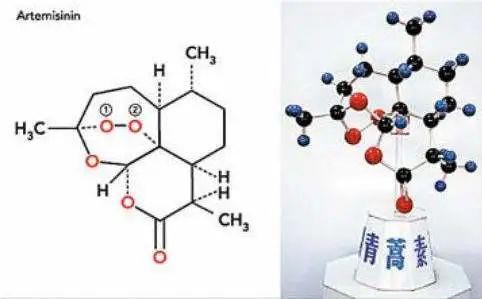

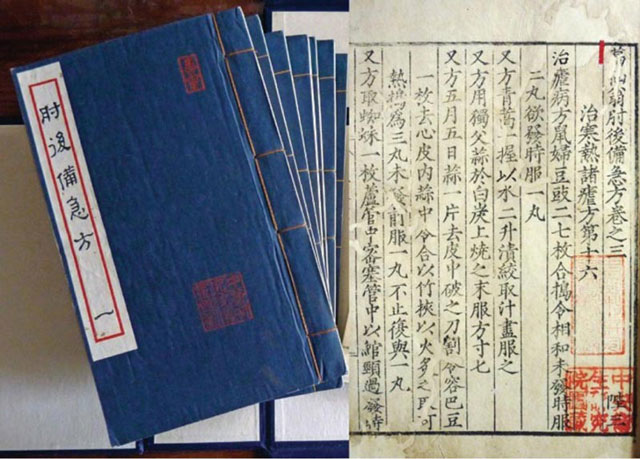

A. New practices of TCMKThe TRIPs agreement provides only for the minimum requirements of patent protection; therefore, it does not prevents States, including China, from developing sui generis IP rights at the national level for more IP protection of TK.74 One of the prominent proposals with respect to the sui generis IP rights in TK against biopiracy is referred to as the “community patent” rights advocated by Professor Ikechi Mgbeoji.75 In Peru, for instance, legislation requires payment of compensation for use of traditional knowledge in the public domain with the view to redressing inequities for indigenous peoples.76 Some Chinese scholars, by the same token, argued that communal patents over such TCMK already in the public domain as ancient prescriptions may be granted to collectives or other identifiable communities against global biopiracy. Nonetheless, patents on TCMK already in the public domain would not have any effect of incentives to innovate; the innovations have already occurred.77 To make matters worse, it may result in increased costs of access to traditional knowledge for future innovations. In short, patenting TCMK already in the public domain may upset a balance between protection against biopiracy and incentives for innovation.In contrast, neither international law nor common sense supports a stagnant and ossified concept of TCMK; the patent system can, therefore, be used affirmatively or positively to protect TCMK through the grant of patent rights to new and innovative advancements in such knowledge systems provided that they meet the requirements to qualify as patentable inventions under the patent system.78Positive patent protection over new practices of TCMK can be justified in preventing misappropriation biopiracy (biopriacy of category four), given that defensive patent protection, albeit valuable and effective in blocking illegitimate IP rights, does not stop outsiders from actively use or commercial exploitation.79 More importantly, the value of new practices of TCMK is widely recognized and fostered. For example, drug companies, like Marco Polo Technologies, in Bethesda, have sought to apply modern techniques to TCM before launching them in the United States. Indeed, "putting traditional medicine on a scientific footing is vital to its continued success in the West," especially in the face of institutional resistance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the US.80Nowadays, new practices of TCMK, albeit under debate, have been actually carried out in China mainly in three ways as follows:81The first way is to find Therapeutic effective chemicals directly to treat certain diseases by extracting the effective parts or active ingredients Based on or guided by old TCMK. This is currently one of the main forms of promoting traditional Chinese medicine as the leading force of bio-pharmaceutical industry development and also an important way of Chinese medicinal modernization. The most famous example is the discovery of artemisinin for treating Malaria. Youyou Tu, a Chinese medical scientist, made more than 380 extracts from 200 herbs, but no significant results emerged. Finally, inspired by the TCMK in Ge Hong’s A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies, which provided that “A handful of qinghao immersed with 2 liters of water, wring out the juice and drink it all,” she successfully extracted artemisinin (qinghaosu) at a lower temperature from the plant artemisia annua.82 Undoubtedly, the knowledge of using qinghao to treat Malaria has been disclosed and already in the public domain. In some countries, the patenting of existing biological materials, unless they have been genetically altered, has been contested and denied. For example, in United Kingdom -- before the adoption of the referred to European Directive -- the High Court of Appeal had held that the isolation of gene sequences constituted mere discovery and, hence, was not patentable.83 Recently, in Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics, Inc., the Supreme Court of USA concluded that the mere contribution of uncovering the precise location of the gene and separating that gene from its surrounding genetic material is insufficient to render it patentable, whereas purified sequences in cDNA are found nowhere in nature and are thus patentable.

A three-dimensional model of artemisinin

A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies by

Ge Hong (284–346 CE)

Under these circumstances, however, it is arguable that in determining the patentability of plant extracts or purifications, one crucial factor is the inventiveness involved in extraction, isolation or purification, rather than the obscure line of discoveries and inventions. In other words, the granting of these kinds of patents may depend on whether or not, and the extent to which the inventive step requirement is met. Accordingly, if relatively common or obvious processes of extraction or purification are involved, the plant extracts or purifications may not be entitled to product patents or process patents.85 In contrast, if extraction or purification entails sufficient ingenuity, painstaking research, or slow trial and error, patents on such plant extracts or purifications as artemisinin may be justified on the basis of encouraging and rewarding the efforts and innovations involved.86The second way is to improve prescriptions already in the public domain to overcome the original shortage by, for example, increasing the potency and reducing the toxicity. For example, Pingwei powder is recorded in the book “Taiping huimin heji jufang” of Song Dynasty. Later generations have transformed it into the new prescriptions (by adding Costustoot, Fructus amomi).87 However, these new prescriptions, although can be protected as composition patents, are difficult to realized market monopoly, for the substitution of other herbal ingredient in those prescriptions with similar medical effects as well as certain changes of medical applications can successfully avoid existing patent claims under the current patent law.88The third way is to adopt new medium types of ancient prescriptions. Traditionally, the preparation of TCM involves grinding a set of herbs based on the prescription and thereby is quite inconvenient. The modem technology has dramatically transformed this practice. Nowadays, pharmaceutical companies can engage in mass production of traditional Chinese medicine, in the forms of pills, powders or capsules, based on some popular ancient prescriptions. Many of these new "instant Chinese medicines" have appealed to many patients by virtue of convenience and led to great market success for many pharmaceutical corporations. The difficult issue here is whether the new practices of the ancient prescriptions in the form of "instant Chinese medicines" should be protected by patents.89It seems to me that the patentability of two latter new practices of TCMK still hinge primarily on the invent step requirement. A lot of Chinese ancient prescriptions, For example, ,although having been shared for a long time, have not been rigorously tested and accepted by the global medical community for drug use, owing to the strict requirement of drug approval process and the lack of clinical trials. To make matters worse, some ancient prescriptions mixed useful information with exaggerations, myths, and (or) lies.90 Therefore, new practices of TCMK in the form of "instant Chinese medicines", if being tested in clinical trials and serving to ascertain valuable information in ancient prescriptions, may meet the inventive step requirement and become patentable, given that some clinical trials are prohibitively expensive and pharmaceutical corporations should be incentivized to do so by patent monopolizations.91Accordingly, in determining patentability of new practices of TCMK, the “inventive step” requirement seems to assume primary importance.B. The Dilemma about

the Patentability StandardsAdmittedly, new practices of TCMK require novelty, utility and especially inventive genius for patentability; however, it still remains to be determined, for example, “what quantum of innovation amounts to an invention.”92 In effect, the determination of that requisite level of inventiveness is a subjective standard varying from country to country, given that Article 27 of the TRIPs agreement does not mandates a universal standard of “inventive step” 93 Countries worried mainly about biopiracy in the area of TMK may apply a strict standard of inventive step; in contrast, countries that wish to promote patenting in the field of TMK, may adopt a lenient approach to purported inventions based on or derived from TMK. What patentability standards is, therefore, a matter of national policy.94 As for TCMK, it has been suggested that stringent patentability standards can arguably reserve global competitive power onto domestic TCM industries and thereby curb global biopiracy, whereas lax patentability standards may favor the development of domestic TCM industries.95 Nevertheless, given the national treatment principle under Article 27.1 of TRIPs, which provides that both national and foreigners will enjoy equal rights to apply for and obtain patents under such standards,96 it is highly likely that, due to greater technological and financial resources, foreign transnational companies will take an advantage in exploiting lax standards.97In my view, however, while China need modify the patentability standards to reflect the different characteristics of TCMK within the confines of the TRIPs and CBD, stringent patentability standards, especially for new practices of TCMK, is arguably preferable to lax standards on the grounds as follows:First, the lax standards of novelty and inventive step/non-obviousness are clearly undesirable from the point of view of free access to TCMK already within the public domain. Patents ought to be granted only on inventions that bring about substantial –not merely cosmetic-changes to prior arts. Otherwise, society will find, for example, that they will have to bear the cost of reducing access to affordable TCMK goods for health or for future innovations. Accordingly, there is little society may gain by extending legal monopolies to TCMK already in the public domain under the guise of genuine inventions.98Secondly, stringent standards can function better to globally safeguard TCMK against refined biopiracy. Thousands of spurious “new drug” patent, for example, are globally granted each year for minor or sometimes trivial developments on TCMK disclosed or already in the public domain, under a significantly low level of “inventiveness” required, especially in the US.99 Absent internationally-accepted patentability standards for TCMK-based patents, China, as the country of origin, should set stringent patentability standards for TCMK-based inventions as role models for other countries to follow, in order to seize the initiative in the fight against TCMK biopiracy on an international scale.Thirdly, lax standards may discourage TMCK-based innovations and researches. The Regulations on the Protection of New Traditional Chinese Medicines, for example, granted exclusive rights to new TCM under a lower standard of "stable quality and clear medical effect" than that of the current clinical trial; 100 as a result, pharmaceutical companies are not willing to prove these new medicines under a more rigorous and more expensive clinical trial standard, nor are they ready to pay the cost for future researches and innovations.101C. Patent Protection against

Misappropriation BiopiracyIn Chinese medicine practice, single herbal ingredient prescriptions are referred to as danfang whereas multiple herbal ingredients prescriptions are fufang which is more widely used than danfang due to the synergistic effects. A powerful patent protection for a fufang prescription may be obtained as long as the chemical structures of its major active ingredients are identified; nevertheless, this is extremely difficult to achieve given that, unlike Western chemical drugs, fufang is processed from a mixture of herbs with hundreds of thousands of compounds.102 Moreover, substituting for some minor herbal components in a fufang prescriptions may lead to a ‘different’ composition without difference in the overall therapeutic effect. Accordingly, the accused infringers may defend on the ground that the substituted herbal ingredient adds new chemical compounds into the drug composition, thereby performing different functions;103consequently, many pharmaceutical companies would reject investments in new practices of TCMK in favor of copying successful prescriptions with some minor changes. In other words, if there is a great risk for a first company to commercialize the TMCK for the reason that the company needs to pay the necessary cost to bring it to the market, without stronger patent protection, once TMCK-based innovations become popular, other companies could free ride the first company's efforts.104A feasible solution is a modification to the rules of specification for fufang prescriptions. That is, at the time of drafting the application, the specification should divide the compositions into several groups and (1) specify the composition with the most principal herbal ingredients in the independent claim; (2) specify the compositions with additional herbal ingredients as dependent claims;105 more importantly, the specification should disclose any “functional equivalent” at the time of drafting.Furthermore, the doctrine of equivalents should be applied to determine the scope of ‘equivalents’ in Chinese fufang prescriptions. ‘similarities’ rather than ‘identity’ should be compared. That is, unless the ‘similarities’ of the herbal drugs are changed (for example, substitution of a principal herbal ingredient in a fufang drug would alter its therapeutic effects and potential side effects), the substitute should be considered as an ‘equivalent’ and within the scope of the claims.106Conclusion

Developing countries may quite reasonably perceive the negotiations on Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreements as industrialized countries in the North working together to strengthen protection for their intangible goods while ignoring biopiracy of TK of the majority of the world. In light of their continued interest in improving global protection for intellectual property, any arguments put forth by industrialized countries to dispel the need for traditional knowledge protection may appear to be contradictory and self-serving. Regrettably, what seems to be absent is an instrumentalist analysis of global biopiracy in light of the objectives and regimes of the patent system. In this article, accordingly, I instance TCMK as an illustration as to how patent regimes under the TRIPs and TK biopiracy interplay globally and how proposed patent defensive protection or positive protection of TK can be used against global biopiacy. In essence, a more balanced and flexible approach to patent regimes with respect to TCMK, in light of competing values and interests, is articulated in the growing controversy over the safeguard TK against global biopriacy.

Footnotes:

[1] Benjamin Liu, “Comment, Past Cultural Achievement as a Future Technological Resource: Contradictions and Opportunities in the Intellectual Property Protection of Chinese Medicine in China” (2003) 21 UCLA Pac. Basin L. J. 75 at 78 .

[2] See Leung AY, “Traditional Toxicity Documentation of Chinese Materia Medica an Overview” (2006) 34:4 Toxic OL PATHOL 319 at 319-26. (Huangdi Neijing, the oldest Chinese medical text, has been treated as the fundamental doctrinal source for TCM for more than two millennia).

[3] Nigel Wiseman, Craig Mitchell &Ye Feng, “Shang Han Lun: Cold Damage, Translation & Commentaries” (2001) 60:3 J. ASIAN STUD 843 at 843-45.

[4] Janet Woodcock, Joseph P. Griffin & Rachel E. Behrman, “Development of Novel Combination Therapies” (2011) 64:3 N ENGL J MED 985 at 985-87.

[5] Mpazi Sinjela & Robin Ramcharan, “Protecting Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Medicines of Indigenous Peoples through Intellectual Property Rights: Issues, Challenges and Strategies” (2005) 12:1 Int'l J on Minority & Group Rts 1 at 10.

[6] World Health Organization, “WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014-2023” (WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data).

[7] Supra note 5 at 10.

[8] Ibid at 8-10.

[9] CAS, a division of the American Chemical Society, is dedicated to the ACS vision of improving people's lives through the transforming power of chemistry.

[10] Rising drug resistance, partly caused by misuse of medicines, has rendered several antibiotics and other life-saving drugs ineffective.

[11] Michael Balick & Paul Alan Cox plants, Peoples and Cultures: the Science of Ethnobotany (New York: Freeman and Company, 1996).

[12] Edward N. Johnson, “Traditional Medicine for Modern Times: Facts and Figures” (30 June 2015), online: Sci Dev Net

[13] Ikechi Mgbeoji, Global Biopiracy: Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006) at 13.

[14] See Megan Dunagan, “Bioprospection Versus Biopiracy and the United States Versus Brazil: Attempts at Creating an Intellectual Property System Applicable Worldwide When Differing Views Are Worlds Apart-and Irreconcilable?” (2009) 15 L& Bus Rev AM 603 at 620 (asserting biopiracy tantamount to thievery).

[15] Daniel F. Robinson, Confronting Biopiracy (London: Earthscan, 2012) at 45.

[16] David Rothschild, Protecting What’s Ours: Indigenous Peoples and Biodiversity (Oakland, CA: South & Meso-American Indian Rights Center 1997) at 116.

[17] See e.g. Lester I. Yano, “Protection of the Ethnobiological Knowledge of Indigenous Peoples” (1993) 41 UCLA L Rev 443 at 445 (arguing that permitting drug developers to profit off indigenous knowledge without compensating indigenous practitioners "is unfair and hypocritical."); David Conforto, “Traditional and Modern-Day Biopiracy: Redefining the Biopiracy Debate” (2004) J Envtl & Litig 357, at 365 (acknowledging the perceived unfairness of geographic restrictions on prior art).

[18] Stephen R. Munzer & Kal Raustalaia, “The Uneasy Case for Intellectual Property Right in Traditional Knowledge” (2009) 27 Cardozo Arts & Ent LJl 37 at 76.

[19] Supra note 15 at 102-04. According to Professor Graham Dutfield, “it seems that protecting traditional knowledge has the potential to improve the performance of many developing countries economics by greater commercial use and increasing exports of traditional knowledge related products.”

[20] Lin Peng, “Strike a Balance between Intellectual Property Protection of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Access to Knowledge” (2014) 7 Tsinghua China L Rev 271 at 302.

[21] WIPO, Intergovernmental Comm. on Intellectual Property & Genetic Res., Traditional Knowledge and Folklore, Consultation Paper: Recommendations on the Recognition of Traditional Knowledge in the Patent System P 15, WIPO/GRTKF/IC/13/7 Annex (Sept. 18, 2008) [hereinafter WIPO, Recognition of Traditional Knowledge].

[22] WIPO, Intergovernmental Comm. on Intellectual Property & Genetic Res., Traditional Knowledge and Folklore, Consultation Paper: Recommendations on the Recognition of Traditional Knowledge in the Patent System P 15, WIPO/GRTKF/IC/13/7 Annex (Sept. 18, 2008) [hereinafter WIPO, Recognition of Traditional Knowledge].

[23] Carlos Correa, Protection and Promotion of Traditional Medicine - Implications for Public Health in Developing Countries (Geneva, Switzerland: South Center, 2002).

[24] Supra note 15 at 58-59.

[25] Supra note 13 at 13.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ryan Abbott, “Documenting Traditional Medical Knowledge” (2014) World Intellectual Property Organization, Available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=2406649.

[28] Supra note 13 at 13, 33, 122.

[29] Mgbeoji, Ikechi "Patents and Traditional Knowledge of the Uses of Plants: Is a Communal Patent Regime Part of the Solution to the Scourge of Bio Piracy" (2001) 9:1 Ind J Global Leg Stud 9 at 174-75.

[30] Supra note 13 at 33.

[31] Gary Stix, “Legal Circumvention: Molecular switches provide a route around existing gene patents” (2002) Scientific American. This article also explores the use of “zinc finger proteins” to switch genes on and off, which are perceived as sufficiently novel for a new patent.

[32] Diamond v Chackrabary 447 US 303 (1980).

[33] Thomas Kiley, “patents on random complementary DNA Fragments?” (1992) 14 Science American 915.

[34] Correa, C.M., Intellectual Property Rights, the WTO and Developing Countries: The TRIPS Agreement and Policy Options), (London: Zed Books, 2000) at Chapter VI.

[35] Patent Act RSC 1985, C P-4 Section 28.2 (1) (in Canada or elsewhere).

[36] America Invent Act, 35 USC § 1-390 (2011).

[37] Such an unsatisfactory state of affairs is also present in Japan.

[38] Patents USC 35 §102 (2012).

[39] Ryan Levy & Spencer Green, “Pharmaceuticals and Biopiracy: How the America Invents Act May Reduce the Misappropriation of Traditional Medicine” 23 U Miami Bus L Rev 401 at 419.

[40] Ibid at 417-422.

[41] See Supra note 18 at 81-82.

[42] Supra note 34.

[43] Xinsheng Wang and Albert Wai-Kit Chan, “Challenge and Patenting Strategies for Chinese Herbal Medicine” Wang et al Chinese Medicine(24 May 2010) online:

[44] Samuel Oddi, “TRIPS : Natural Rights and a "Polite Form of Economic Imperialism" (1996) 29 Vand J Transnat’I L 415.

[45] B. Mandelker, “Indigenous People and Cultural Appropriation: Intellectual Property Problems and Solutions” (2000) 16 CIPR 367 at 367-401.

[46] See J. Janewa OseiTutu, “A Sui Generis Regime for Traditional Knowledge: The Cultural Divide in Intellectual Property Law” (2011) 15:1 Marq Intell Prop L Rev 147 at 190.

[47] Ibid at 214.

[48] WIPO IGC, The Protection of Traditional Knowledge: Revised Objectives and Principles, WIPO Doc. WIPO/GRTKF/IC/9/5 (2006)

[49] Paul Kuruk, “Goading a Reluctant Dinosaur: Mutual Recognition Agreements as a Policy Response to the Misappropriation of Foreign Traditional Knowledge in the United States” (2007) 34 Pepp L Rev 629 at 647–649.

[50] Graham Dutfield, Protecting Traditional Knowledge: Pathways to the Future (Geneva, Switzerland: ICTSD, 2006) at 21-22.

[51] Madhavi Sunder, “The Invention of Traditional Knowledge” (2007) 70 Law & Contemp Probs 97 at 106.

[52] Supra note 46 at 190.

[53] Supra note 15 at 77-78.

[54] Supra note 46 at 201-202.

[55] Supra note 15 at 78.

[56] United States Constitution grants Congress the power "To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries" ; See also Feist Publications,Inc v Rural Telephone Service Company, 499 US 340 (1991) [ Feist]

[57] Supra note 15 at 124.

[58] Supra note 46 at 214.

[59] Outsiders may mean parties other than the customary custodians of the knowledge or resources.

[60] “Intellectual Property and Traditional Knowledge” World Intellectual Property Organization, WIPO Publication 920(E) at 28.

[61] Ibid at 29.

[62]C. Correa, Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Property: Issues and Options Surrounding the Protection of Traditional Knowledge (Geneva : Quaker United Nations Office, 2001) at 492.

[63] Supra note 50 at 44.

[64] Jay Erstling, “Using Patents to Protects Traditional Knowledge” (2009) 15 Tex Wesleyan L Rev 295 at 324-25.

[65] Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) system is a system under the CBD framework to regulate the conditions for access to and use of genetic resources and the sharing of benefits from their utilization with ILCs.

[66] Supra note 64 at 13.

[67] Dagne Tesh, “Protecting Traditional Knowledge in International Intellectual Property Law: Imperatives for Protection and Choice of Modalities” (2014) 14 J Marshall Rev Intell Prop 25.

[68] See Supra note 20.

[69] T. Kongolo & F. Shyllon, “Panorama of the Most Controversial IP Issues in Developing Countries” (2004) 26:6 Eur IP Rev, 258 at 260.

[70] See Supra note 64 at 12; Supra note 64 at 319-22.

[71] See About TKDL, http:// www.tkdl.res.in/tkdl/langdefault/common/AboutTKDL.asp (last visited Feb. 27, 2009); China TCM Patent Database, http:// chmp.cnipr.cn/englishversion/help/help.html (last visited Feb. 23, 2009).

[72] In some scenarios, defensive protection may actually undermine the interests of TK holders, particularly when this involves giving the public access to TK which is otherwise undisclosed, secret or inaccessible. In the absence of positive rights, public disclosure of TK may actually facilitate the unauthorized use of TK which the community wishes to protect. See Rohaida Nordin, Kamal Halili Hassan & Zinatul A. Zainol, “Traditional Knowledge Documentation: Preventing or Promoting Biopiracy” (2012) 11:22 J Soc Sci & Hum 20.

[73] See Mangala Anil Hirwade, “Protecting Traditional Knowledge Digitally: A Case Study of TKDL” (2013) [unpublished archived at RTM Nagpur University library]; Supra note 15 at 151-53.

[74] In 2007, China accepted the Agreement On Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Right (the TRIPs).

[75] Supra note 13 at 162-76.

[76] Supra note 23.

[77] Supra note 18 at 73.

[78] See WIPO Recognition of TK para 10; Yinliang Liu, “IPR Protection for New Traditional Knowledge: With a case Study of Traditional Chinese Medicine” (2003) EIPR 194.

[79] Supra note 60 at 28.

[80] Supra note 5 at 10.

[81] Song Xiaoting, “New Problems of Intellectual Property during Innovation of Traditional Chinese Medicine” (2011) 13:3 Mode Tradit Chin Med Mater Med 466 at 467.

[82] Youyou Tu, “The Discovery of Artemisinin (qinghaosu) and Gifts from Chinese Medicine” (2011) 17:10 Natural Medicine (Commentary on Lasker~DeBakey Clinical medical research award).

[83] Supra note 23.

[84] Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics, Inc., 133 S Ct 2107 (2013).

[85] See also Supra note 13 at 144.

[86] Supra note 23.

[87] Supra 80 at 467.

[88] Ibid at 467-68.

[89] Supra note 20 at 296.

[90] Ibid at 297.

[91] Ibid at 299-300.

[92] Supra note 13 at 103.

[93] Ibid at 136-37.

[94] Supra note 23.

[95] Benjamin Liu, “Past Cultural Achievement as a Future Technological Resource: Contradictions and Opportunities in the Intellectual Property Protection of Chinese Medicine in China” (2003) 21:1 Pacific Basin Law Journal 75 at 88-89.

[96] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 15 April 1994, (entered into force on January 1, 1995); reprinted, 33 ILM 1197 (1994).

[97] See Supra note 51 at 106; Supra note 23.

[98] Supra note 46.

[99] John H. Barton “Intellectual Property Rights: Reforming the Patent System” (2000) 287 Science 1933.

[100] [Regulations on the Protection of New Traditional Chinese Medicines] (promulgated by the St. Council, Oct. 14, 1992, effective Jan. 1, 1993) art. 3 (Chinalawinfo).

[101] Supra note 20 at 288-89.

[102] Supra note 43.

[103] Xinsheng Wang, Jiaher Tian & Albert Wai-Kit Chan, “Scope of Claim Coverage in Patents of fufang Chinese Herbal Drugs: Substitution of Ingredients” Wang et al Chinese Medicine (30 June 2011) online:< www.cmjournal.org/content/6/1/30>.

[104] Supra note 20 at 287, 300.

[105] Supra note 43.

[106] Supra note 100.

Copyright 环太平洋法律&商业协会 沪ICP备2023004680号-1